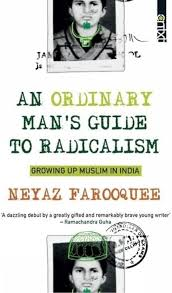

Surviving Identity: A Review of An Ordinary Man's Guide to Radicalism by Neyaz Farooquee

In his book An Ordinary Man's Guide to Radicalism: Growing Up Muslim in India, journalist Neyaz Farooquee tells his own tale that is also politically relevant. The book tells his life story as a young Muslim Indian from a middle-class background, mostly in Delhi's Jamia Nagar, through significant events in the country like the Batla House confrontation in 2008. The book is significant because it tells a reality in a straightforward, honest, and unobtrusive manner that tends to be overlooked or distorted in public debate: What is it like to be a Muslim in a country where your identity can immediately become a problem?

We are presented with the insider's view of fear, ambition, prejudice, and hope through Farooquee's recollections. It is not a tale of extremism. Ironically, it is a tale of how not to get radicalized in reaction to every provocation. It is the tale of how an average man manages in exceptional times by clinging to decency, to dignity, and to dreams.

A Life Along a Fault Line

Farooquee was brought up in Jamia Nagar, Delhi. The locality quickly changed after the Batla House encounter on 19 September 2008. Two suspected terrorists were killed and one policeman was killed. This generated a lot of fear and mistrust in the entire locality. The residents were referred to as "sympathizers," and the media began referring to the locality as "a den of terror."

To him, this was no news—it was home. He was living a couple of lanes away from where the police operation was happening. His family, like thousands of families, started living in the shadow. Police vans, journalists, and surveillance were the order of the day. Doors were being knocked on in the middle of the night. Families were terrified to answer unknown numbers. Suspicion hung heavy in the air, and normal life became extraordinary.

The most frightening aspect? It's arbitrary. Any young Muslim male in the community was subject to being picked up, interrogated, and tagged. Farooquee understood that individuals such as himself, who believed in the Constitution as a lifestyle and attempted to adhere to the law, were not safe.

Everyday Dreams, Extraordinary Challenges

Farooquee's story is simple to relate to for anybody who comes from a poor background and has ambitions to go a long way. He was born in a tiny village in Bihar but moved to Delhi with his parents in pursuit of greater opportunities. His father was a clerk and mother a housewife; they worked hard to give him an education.

As with millions of Indian families, they believed education was the key to progress in life. Farooquee was a studious student, managed to get into Jamia Millia Islamia, and attempted to be a good student. His path was not without hurdles, however. The system, the individuals surrounding him, and even some liberal do-gooders at other times looked at him not just as a student, but as "a Muslim student."

He remembers being turned down for a job as a journalist following a positive interview. Then a member of the shortlist committee informed him that his name prejudiced him against getting the job. In a different case, when he tried to rent an apartment in Delhi, he was asked whether he would "have a lot of Muslim guests" visiting him.

To most people, they are minor embarrassments. But to one who has to endure them daily, they are reminders that being good may not be enough if your name is Neyaz and not Neeraj.

The Burden of Stereotypes

One of the recurring themes in the book is the weight of stereotypes. He has been questioned at airports, watched on trains, received gratuitous advice to "be careful," and been asked questions like "Are Muslims taught to hate Hindus?"—Farooquee has had to bear all this.

He remembers telling another student who asked him with genuine curiosity, "Are Muslims more violent in nature?" Farooquee did not become angry but became saddened. These stereotypes are not just offensive—they are harmful. They underpin profiling, arrest, and discrimination, and make people feel isolated.

There is one searing moment. Even during the Batla House crisis, Farooquee's Hindu neighbour, an old friend, refused to speak to him. No fight, no justification, just silence. This silent estrangement is more agonizing than oral recrimination. It informs minorities that, however peaceful you are, however educated you are, however law-abiding, people will always doubt your loyalty.

When Belonging Is a Struggle

The struggle for belonging is central to this memoir. Farooquee describes the unseen walls that divide communities. Even cosmopolitan Delhi confines Muslims in "ghettos" such as Jamia Nagar—not by choice, but by default. Other neighbourhoods will not rent to them. Brokers dissuade them. Landlords cheat them.

The author describes how this separation increases bias. When Muslims live in the same area, people say they are making “mini Pakistans.” When they attempt to move to different places, they are refused. And when they stand up for their rights, they are called “radical.”

It's a lose-lose situation. Belonging, which is a fundamental right in a democracy, is a daily struggle. The fact that so many Muslims like Farooquee are still clinging to the dream of India, even after all of this, is not only surprising—it's courageous.

The Feelings That Arise from Being Watched

Farooquee's prose is strongest when it delves into the emotions of a young man under surveillance. From security checks at the metro station to interrogation at airports, to being pulled over at random on the highway, the book reveals the psychological weight of living in suspicion.

He speaks of being afraid to leave the house, practicing answers in case the police stop him, and avoiding fights so they don't get misconstrued. It's not fear—it's fatigue. Being in watch mode all the time, being judged all the time, and being forced to explain yourself all the time fatigues you.

He explains, "I was just a student trying to graduate. But I felt like I had to be my own lawyer, spokesperson, and bodyguard." The pain is quiet but enduring. It indicates that violence is not necessarily done by guns. It may be done by glances, silences, and policies.

Life After Batla House: Politics, Protests, and Opportunities

The Batla House encounter was an eye-opener for Farooquee. It awakened many young Indian Muslim youth. Farooquee discusses how Jamia Millia students began to organize protests, calling for a proper investigation into the encounter. The students came to understand for the first time that just being "good" or "quiet" would not do. They needed to speak out. They needed to protest.

This political awakening is one of the most inspiring parts of the book. Farooquee was part of a generation that was starting to take back the Muslim voice—not with arms, but with constitutional rights, protest, and literature. He became a journalist not to propagate an ideology, but to tell the truth. His articles in newspapers like The New York Times, Al Jazeera, and The Indian Express stand testament to this commitment.

He also gives accounts of solidarity—non-Muslim allies who held their ground, educators who resisted on behalf of students, and communities that made alliances. Those accounts remind readers that there is still hope in the cracks of despair.

Personal to Political: How Identity Shapes Politics

Farooquee's book is deeply political. Each event—from not being offered a place to live to being overlooked by employment recruiters—illuminates how rules and biases impact real people. Farooquee denounces the media for labeling Muslims suspects without cause. He denounces politicians who use divisive language to polarize voters too. He does so, however, in a nonviolent fashion, not an angry one.

He cautions against the pull of victimhood or withdrawal. Although he knows why Muslims retreat from the public or retreat inward, he encourages them to challenge the system, vote, participate, and speak out. Silence, he argues, only reinforces the stereotype.

The memoir does not provide easy answers, but it demands honesty on the part of Muslims and non-Muslims. It demands that the country examine how it treats its largest minority.

Style, Tone, And Why This Book Remains Relevant Today

Farooquee's writing is straightforward, simple, and full of feeling. It is not technical jargon or political philosophy. It is sitting down and having a chat with a friend. The tone is gentle, even on hard topics. That is what makes it so powerful.

This is not a book on terrorism. It's a book on the way in which people wrongly accused of backing terrorism live. It's a book on the way in which being Muslim in India is not risky—but is made to appear risky.

In a world where Muslims are stereotyped daily in the movies, political rhetoric, and newsrooms, An Ordinary Man's Guide to Radicalism is a much-needed counter-narrative. It humanizes and demystifies the dehumanized. It challenges readers to go beyond names and attire, and to glimpse the person behind that.

Significance Today

Since the book was released, India has grown even more polarized. Community politics, the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), the NRC debates, and rising community violence make this memoir even more applicable. It is not a 2008 book—it also stands for 2024.

The fears that Farooquee wrote about have only grown. But the courage he showed—by writing this book and by staying firm—continues to inspire. For every young Muslim who is unsure if he or she belongs, this book is a guide. It is not a guide to radicalism, but a guide to living a good life.

Conclusion: An Appeal to Understanding, Not Sympathy

An Ordinary Man's Guide to Radicalism is not advocating violence. It is advocating listening. Understanding. Thinking through. Neyaz Farooquee is not requesting preferential treatment. He is requesting fairness. He is requesting the nation to see its minorities not as puzzles to be solved, but as individuals to be embraced. In sharing his story, he shares the story of many people. His voice is not loud, but it resonates. His pain is not dramatic, but it stays with you. His hope is not simple—it is strong, because it exists even with all that happens. In an era marked by loud hate, this unassuming book is a gesture of defiance.

Comments

Post a Comment